Kidney stones are small, hard deposits that form in the kidneys and can cause severe pain when they move or block the flow of urine. Understanding the different types of kidney stones helps in choosing the right treatment and preventing them from coming back 1.

Kidney stones are solid "crystals" made from minerals and salts that normally stay dissolved in the urine. When the urine becomes too concentrated, these minerals can stick together and form stones of different sizes, from a grain of sand to a large stone filling the kidney 1.

Most stones start in the kidney but can move into the ureter (the tube from kidney to bladder), where they may get stuck and cause pain, blood in urine, or infection. Many small stones can pass out on their own, while larger or complicated stones may need procedures by a urologist 1.

How kidney stones form?

Urine contains water plus waste chemicals like calcium, oxalate, uric acid and others. If there is too little water or too much of these substances, crystals can form and slowly grow into stones 2.

Other factors such as repeated urinary infections, certain medical conditions, family history, and some medicines can also increase the risk of stone formation. Over time, stones can grow silently in the kidney until they move or block the flow of urine 1.

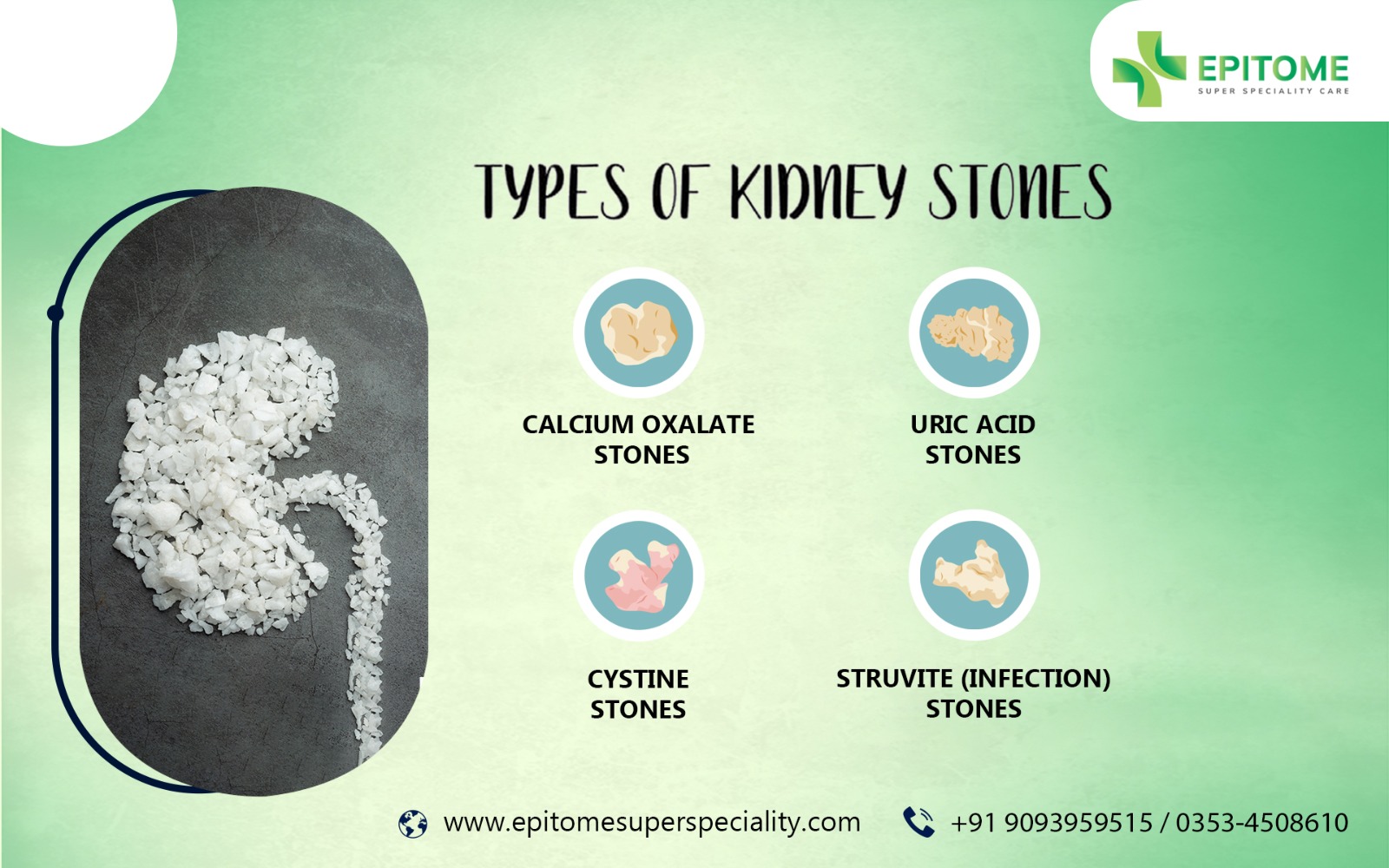

Types of kidney stones 3 :

There are four main types of kidney stones, plus some rare types. Knowing the stone type guides diet changes, tests, and medicines to prevent recurrence.

Calcium oxalate stones 1,3 :

Calcium stones are the most common, and most of them are made of calcium oxalate. They often form when urine has high levels of calcium and oxalate, and low levels of citrate, which is a natural "stone blocker."

Risk factors include low fluid intake, high salt intake, frequent animal protein, some high-oxalate foods, obesity, and certain medical conditions like hyperparathyroidism. Diet and medicines can significantly reduce the chance of these stones coming back.

Uric acid stones 1 :

Uric acid stones form when urine is too acidic. They are more common in people who eat a lot of red meat and organ meat, have gout, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, or chronic dehydration.

These stones can sometimes be dissolved by medicines that make the urine less acidic and by drinking more fluids. Reducing purine-rich foods (such as certain meats and seafood) also helps lower uric acid levels.

Struvite (infection) stones 1 :

Struvite stones are linked to certain types of urinary tract infections (UTIs), usually caused by bacteria that change the urine pH. They tend to grow quickly and can become very large, sometimes filling much of the kidney.

These stones are more common in women and in people with repeated or long-standing UTIs or structural urinary problems. Successful management usually needs both stone removal and careful treatment and prevention of infections.

Cystine stones:

Cystine stones are rare and occur in people with an inherited condition called cystinuria, where excess cystine (an amino acid) leaks into urine and forms crystals. They often start at a young age and tend to recur throughout life. 1

Prevention focuses on very high fluid intake, keeping urine less acidic, and in some cases using special medicines that help keep cystine dissolved. Close follow-up with a urologist and sometimes a nephrologist is usually needed 4.

Less common stones 1 :

Some patients have stones made of calcium phosphate, which are more often linked to certain metabolic or kidney tubular problems and very alkaline urine. Medications, diet changes, and checking for underlying conditions help in these cases.

Very rare stones can form from certain medicines (such as some HIV drugs or diuretics) or from unusual metabolic diseases. Your doctor may send a passed or removed stone for analysis to find the exact type.

Symptoms patients may experience

Common symptoms when a stone moves or blocks urine flow include:

- Sudden, severe pain in the side, back, lower abdomen, or groin, often coming in waves 5.

- Blood in urine, which may make it look pink, red, or brown 6.

- Burning or pain while passing urine, and frequent urge to urinate 6.

- Nausea and vomiting, especially with severe pain 5.

If infection is present, you may have fever, chills, and feeling very unwell. Some small stones may cause only mild discomfort or be found incidentally on an ultrasound or CT scan done for another reason.

How kidney stones are diagnosed 1,5,6 :

Doctors use a mix of history, examination, and tests to diagnose kidney stones. The main tools are scans and urine tests.

- Ultrasound (USG): Uses sound waves to look at the kidneys and bladder; has no radiation and is often used first, especially in pregnancy.

- CT scan: A non-contrast CT of kidneys, ureters and bladder (CT KUB) is very accurate in finding stones and their size and location.

- X-ray (KUB): May show some types of stones, but not all.

- Urine tests: Check for blood, infection, crystals and measure chemicals in 24-hour urine to understand why stones are forming.

- Blood tests: Assess kidney function and levels of calcium, uric acid, and other factors.

If possible, the passed or removed stone is sent for analysis, which helps tailor prevention strategies.

Management and treatment 4,5 :

Treatment depends on stone size, location, symptoms, infection, kidney function, and patient factors. Many small stones can pass naturally with medicines and fluids, while larger or complicated stones need procedures.

Hydration

Drinking enough fluid is one of the most important parts of stone management and prevention. Most guidelines advise aiming for urine output of at least about 2.0-2.5 liters per day, which usually needs about 2.5-3.0 liters of fluid intake unless restricted by other medical conditions.

Water is the best choice; sugary drinks and excess cola should be limited. Your doctor may modify fluid goals if you have heart failure or advanced kidney disease.

Pain management

Pain control is essential when a stone moves. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or other painkillers are commonly used, sometimes by injection in the emergency room.

Stronger medicines may be needed for short periods in severe pain, always under medical supervision. Good pain control also helps you stay mobile and drink fluids.

Medical expulsive therapy

Medical expulsive therapy uses medicines, usually alpha-blockers such as tamsulosin, silodosin to help relax the ureter and improve the chance of passing a small stone. This approach is generally considered for stones of moderate size in the ureter, if there is no infection or severe obstruction.

Your urologist will decide how long to wait for spontaneous passage and when to step up to a procedure if the stone does not move.

Diet modification

Diet changes depend partly on the stone type and urine test results. In general, a balanced diet with normal calcium, reduced salt, moderate animal protein, and plenty of fruits and vegetables is recommended.

For some patients, limiting very high-oxalate foods or high-purine foods (for uric acid stones) is useful. Your doctor may suggest a dietitian referral for personalized advice.

ESWL (shockwave lithotripsy)

Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) uses focused sound waves from outside the body to break stones into smaller pieces that can pass in the urine. It is usually done as a day-care procedure under sedation or light anaesthesia.

ESWL works best for certain stones in the kidney or upper ureter, usually below a specific size. You may have some blood in urine and colicky pain as fragments pass over the next few days.

URS / laser treatment

Ureteroscopy (URS) involves passing a thin scope through the urethra and bladder into the ureter or kidney to see and treat the stone. The stone is usually broken with a laser and removed in pieces or allowed to pass as dust.

URS is useful for stones in the ureter and kidney that are not suitable for ESWL or have failed earlier treatment. A temporary internal stent may be placed to help urine flow and reduce swelling, which is later removed in the clinic.

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL)

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) is a minimally invasive surgery for large or complex kidney stones. The surgeon makes a small cut in the back, creates a channel into the kidney, and uses instruments to break and remove the stone.

PCNL is usually recommended for very large stones, staghorn (branching) stones, or when other methods are unlikely to clear the stone completely. Hospital stay is slightly longer, and recovery is guided closely by the urology team.

When emergency treatment is required 4,6 :

Immediate medical attention is needed if:

- You have severe flank or abdominal pain that is not improving with medicines.

- You have fever, chills, or feel very unwell along with stone symptoms (this could mean infection with blockage, which is an emergency).

- You are unable to pass urine, or the urine output suddenly drops.

- Pain occurs in a person with a single kidney, transplanted kidney, or known poor kidney function.

In these situations, urgent drainage (such as a stent or nephrostomy tube) and antibiotics may be life-saving.

Prevention strategies 4 :

Preventing another stone is just as important as treating the current one. Your urologist will suggest general measures for all stone formers and specific steps based on stone type and test results.

Diet tips and hydration goals 2

- Aim for total fluid intake of about 2.5-3.0 liters per day (unless restricted), targeting urine output more than 2.0-2.5 liters daily.

- Prefer water; limit sugary drinks and avoid excessive cola and high-sugar beverages.

- Include plenty of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and adequate fibre.

Salt restriction 4

High salt intake increases calcium loss in urine and raises stone risk. Most guidelines recommend limiting salt to roughly 4-5 grams of table salt (sodium chloride) per day, including hidden salt in packaged foods.

Cooking with less salt, avoiding added salt at the table, and cutting back on salty snacks and processed foods are simple, effective steps.

Oxalate moderation 4

For patients with calcium oxalate stones and high urinary oxalate, moderating very high-oxalate foods may help. Examples include spinach, beetroot, nuts, chocolate, and strong black tea, which may need to be limited rather than completely avoided.

Taking normal dietary calcium (from food) with meals can bind oxalate in the gut and reduce its absorption. Very low calcium intake is usually not advised, as it may increase both stone risk and harm bone health.

Protein moderation 4

Excess animal protein (red meat, processed meat, large quantities of poultry or fish) can increase calcium and uric acid in urine and make urine more acidic. Most guidelines suggest moderate animal protein rather than very high-protein diets for stone formers.

Plant-based proteins (such as lentils and beans) can be included, but total protein intake should match your health status and doctor's advice.

Recurrence prevention and medical therapy 7

For patients with repeated stones or high-risk features, medicines can lower the chance of another stone. These are usually started after metabolic evaluation and tailored to your stone type.

- Potassium citrate: Helps make urine less acidic and increases citrate, which protects against calcium and uric acid stones. It is commonly used in patients with low urinary citrate or uric acid stones.

- Thiazide diuretics: Reduce calcium loss in urine and are used for patients with high urinary calcium and recurrent calcium stones.

- Allopurinol (or similar drugs): Lower uric acid levels and may be used in patients with high uric acid and uric acid or mixed stones.

For struvite stones, controlling and preventing UTIs is crucial, and sometimes special medicines that block bacterial enzymes are considered in selected cases. Cystine stone formers may need high fluid intake, alkali therapy, and specific drugs that bind cystine.

When to see a urologist

You should consult a urologist if:

- You have symptoms suggestive of a stone (colicky pain, blood in urine, repeated burning or infections).

- You have been told you have a stone on ultrasound or CT, even if pain is mild or absent.

- You have recurrent stones, a family history of stones, or other kidney problems.

- You already had stone surgery or ESWL and want to know how to prevent future stones.

Early specialist input helps protect kidney function, control symptoms, and design a long-term prevention plan.

References

- Stephen W. Leslie; Hussain Sajjad; Patrick B. Murphy. Renal Calculi, Nephrolithiasis, StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan.

- Kithmini NG, Enakshee J, Sadaf KS, Amelia P, Omar A, Bhaskar KS. The role of fluid intake in the prevention of kidney stone disease: A systematic review over the last two decades. Turk J Urol. 2020 Jun 5;46(Suppl 1):S92–S103. doi: 10.5152/tud.2020.20155

- Naeem B, Jennifer B, Brendan W, Linda L, Kamaljot SK, Marie D, Andrea C, et al. UPDATE – Canadian Urological Association guideline: Evaluation and medical management of kidney stones. Can Urol Assoc J. 2022 Mar 11;16(6):175–188. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.7872

- Türk C, Neisius A, Petřík A, et al. EAU Guidelines on Urolithiasis. European Association of Urology; latest update 2025.

- Cleveland Clinic. Kidney Stones: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment. Cleveland Clinic. 2025.

- Mayo Clinic Staff. Kidney stones: Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. 2025.

- Bhojani N, Paonessa J, Hameed F. Evaluation and medical management of kidney stones. Can Urol Assoc J. 2022;16(6):E295-E305.

This educational content is authored by Dr. Abhishek Kumar Singh (M.B.B.S., M.S.(SURGERY), D.N.B. (Genito Urinary Surgery)), and is intended for patient awareness and public health education. For personalized consultation and kidney stone care, please consult with a qualified urologist.